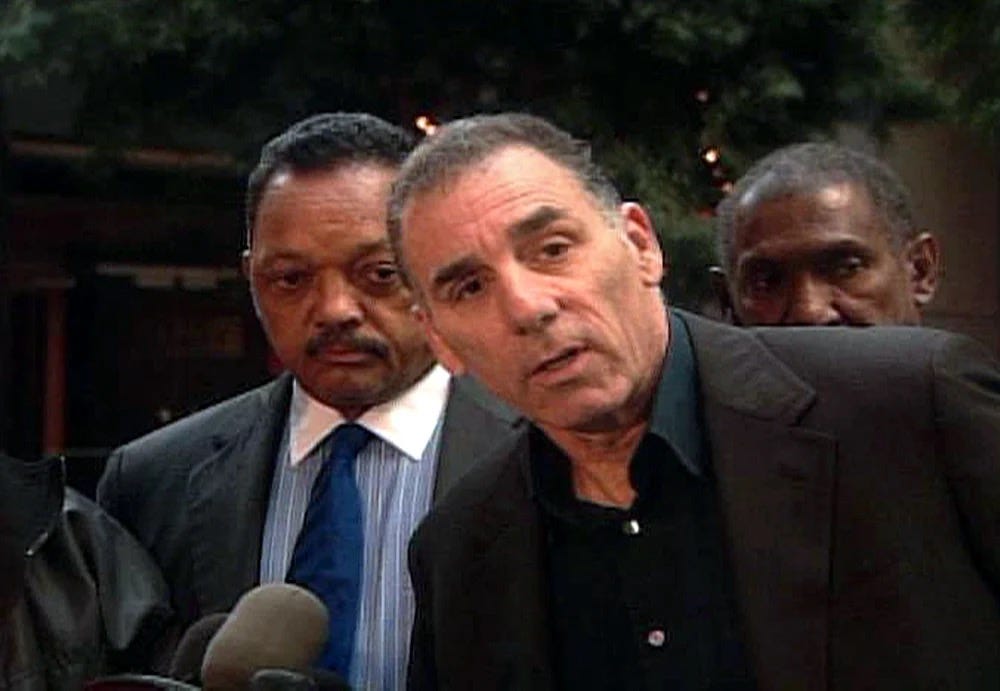

Jesse Jackson Never Forgave MeJackson Died Today. I'm Glad It Wasn't Due to Our Conversation in 2006.When you write a weekly column, not every idea is a winner. When you write a column for the L.A. Times and Time magazine simultaneously, none of them are. Whereas in Buddhism, you acknowledge every passing thought as a byproduct of the mind and dismiss them like passing radio waves, every idea I turned them all into email interview requests. Few called me back. None had called without first emailing. I was sitting at a desk at Time magazine in New York, having moved back for a couple of months to help re-imagine the front section. I was busy doing very important things like telling writers to turn graphs into quizzes and quizzes into graphs. Then my phone rang. Two hours earlier, I’d had an idea. Michael Richards of Seinfeld fame had destroyed his career by calling a black audience member a racial slur during a set at a comedy club. Richards sought out Jesse Jackson and apologized to him. I assumed that I would write something offensive one day, and that when I did, it might take several tense hours before I could get Jesse Jackson on the phone to apologize to him. So I figured I’d call him in advance and pre-apologize. By then, Jackson had accepted apologies from Mexican President Vicente Fox (for saying Mexican immigrants will do jobs that “not even blacks want to do”), the producers of Barbershop (for a Rosa Parks joke in the film), and himself (for calling New York “Hymietown”). Seinfeld was in syndication, Fox served his full two terms, Barbershop had two sequels, and New York was still chock-full of Jews. A Jackson pardon never failed. After putting in a request with Jackson’s staff that I thought they wouldn’t take seriously, I was surprised when my phone rang two hours later with the reverend on the phone. I would be absolved, I thought, in two or three minutes. I was very wrong. When I explained my request, it became clear that this hypothetical offensive thing I might someday do was instead happening right now. “Why should you be offensive?” Jackson asked. “I don’t know why you would do that.” Luckily, as I stammered a response, Jackson smoothly segued into reciting his own agenda. I was not surprised to hear him tell me about America’s lack of concern about Katrina victims, the media ignoring Trent Lott’s return to party leadership, and the dearth of black actors on television (“all day, all night, all white”). I was, however, surprised that it took him nearly four minutes before he mentioned the fact that he worked with Martin Luther King Jr. A smarter man would have thanked Jackson for his time and gotten off the phone. But as I predicted in the very concept of this project, I am not a smarter man. I asked again if he could slip me an indulgence. “I don’t know why you would insist on continuing to bring this up,” he said. Oddly, I was thinking the exact same thing. I explained that I was interested in how a single person can play judge for damage done to an entire group, and why society appoints someone to represent its pain. Then I hoped and prayed that sounded smart. Jackson said that when Richards called him, “I made it clear that I am not the arbiter of apologies.” In fact, he said, “I’m more likely to be called upon to get someone out of a foreign jail than to accept an apology.” Between the foreign arrests and the apologies for racist slurs, being a civil rights leader seemed a lot like parenting rich children. Then Jackson pointed out that listening to confessions is pretty common for someone in his line of work. “When people are distressed, when people are injured, when people need their cases argued, they tend to call a minister,” he explained. “People tend to call someone to give them a listening ear. That’s all. At the end of the day, it’s about providing a service: to alleviate misery.” My future misery, however, was presently unalleviable. “It would be inappropriate,” he finally told me. I was the first person in history to have an apology turned down by Jesse Jackson. But as ridiculous as it seems to have people apologize to Jackson for things they didn’t do to him, and for him to demand apologies for events he wasn’t involved in (Outkast for dressing in Native American outfits; the U.S. for crashing a jet in China) – it does serve a purpose. Confrontation is a necessary part of contrition: Apologizing in a press release to anyone offended makes sense in theory, but it has no stakes. We need to see human emotions expressed by real humans; our catharsis has to come from leaders playing our parts on stage. And Jackson was really good at it. After I finally got off the phone, sweaty and stomach-hurt, I felt like I had been taught a moral lesson. But I was not. Three-and-a-half years later, I wrote a column about immigration that many Indian people found racist. Also, many people who were not Indian. And I had blown my chance to apologize to Jackson. Still, I should have called him. Despite my stupid column idea, I think he would have listened to my apology. And I needed someone to talk to. The world can’t afford to keep losing people we can apologize to. Thank you for paying to read my column. Wait: This is for the people who didn’t pay? Then I owe you nothing. You are the ones contributing to the end of my career. If you want to pay an exorbitant amount of money to get one extra post a month – which often won’t even be that good – upgrade to a paid subscription here: |

Tuesday, February 17, 2026

Jesse Jackson Never Forgave Me

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Benedict's Newsletter: No. 630

In this issue: Scare trades, bubble thinking, AI commerce, telco translation, PE software and PE law, ad agency subscriptions and ...

-

Four Ohio cities ranked in the nation's top 100 best cities for single people, according to a WalletHub survey that considered fact...

-

The Trump administration has launched a new federal initiative called the U.S. Tech Force, aimed at hiring about 1,000 engineers and t...

No comments:

Post a Comment