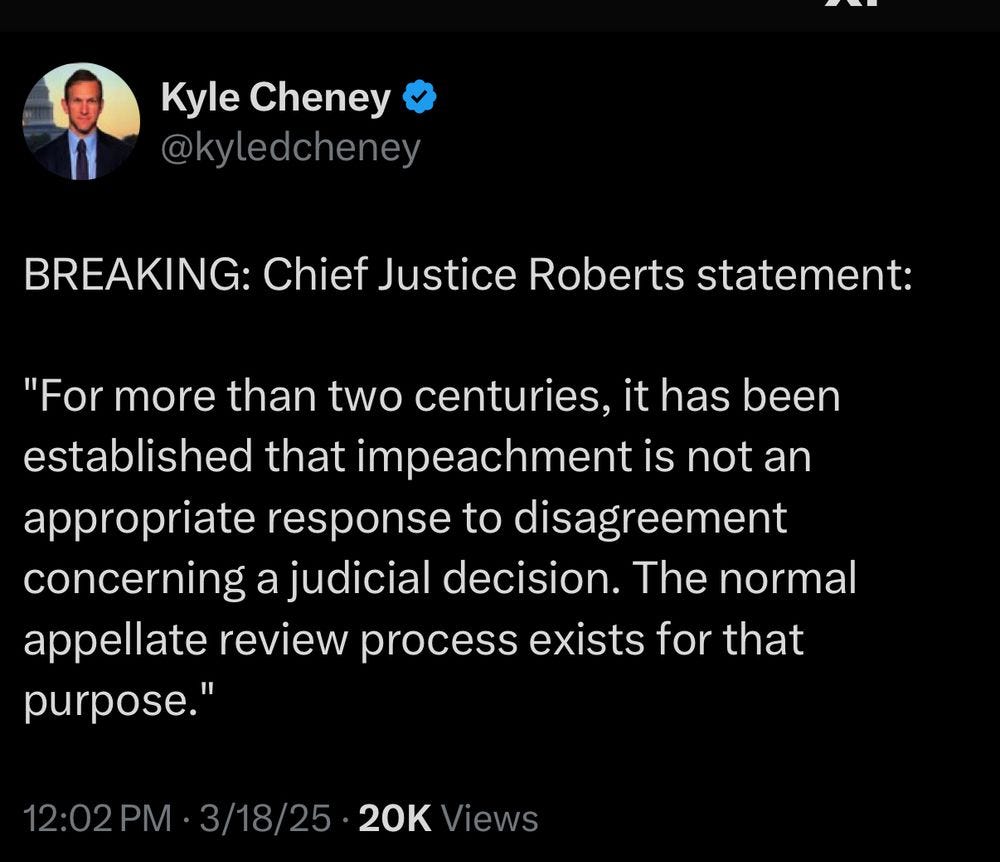

As is the custom, on the last day of the year, Chief Justice John Roberts issued a report on the state of the federal judiciary. Formally titled “2025 Year End Report on the Federal Judiciary,” it starts with this picture. I don’t mean to nitpick, or maybe I do. Either way, it’s an odd choice. A fancy, empty room. History, devoid of humanity. I’m sympathetic to the position the Chief Justice is in. It’s not his job to play politics, and restraint is usually the general order of business. But the past year has not been a normal one. The Chief Justice’s year-end report treats it as though it has been. The past decade has made it clear that our institutions are only as strong as the people in them. That makes this photo a startling choice for a report about the judiciary, albeit likely unintentional. But it’s a marker for what has become increasingly clear: that the majority on this Court has failed to show up in a moment when their institutional voice is desperately needed. The Court has been either unwilling or incapable of meeting the challenge to democracy that Donald Trump poses. The Court has important cases to decide over the next few months. The National Guard ruling over the holiday was a bright spot where the Court temporarily told Trump no. But there are a number of highly significant cases on presidential powers, immigration, gerrymandering and voting rights, and more, still to come this term. The Chief Justice’s report takes the form of an essay about American history, followed by statistics about the Court and its work. You can read the full report here. Roberts begins with the story of Thomas Paine and the publication of Common Sense (interestingly enough, a book I delved into at some length in my book Giving Up Is Unforgivable). He writes, “Paine advanced several key points. A government’s purpose is to serve the people. The colonists should view themselves as a distinctive people—Americans, not British subjects. The colonies had reached ‘that peculiar time which never happens to a nation but once, viz., the time of forming itself into a government.’ And, in view of the foregoing propositions, as an independent nation, the colonists would ‘have it in our power to begin the world over again.’” This explains Roberts’ choice of illustration—the empty room is the Assembly Room at Independence Hall, the place where the Founding Fathers met and approved the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. Roberts spends some time, without any comment about what it might mean, on the notion of patriotism and treason: “The brave patriots who crafted and approved the definitive statement of American independence pledged to support each other and their new nation with ‘our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.’ They understood that the British would view their words and actions as treason. As Franklin reportedly warned, ‘[W]e must, indeed, all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately.’” It’s a quote that, absent any context or explanation, can mean all things to all people. A mark of how carefully this Chief Justice continues to navigate the political moment in a survival-oriented fashion, rather than taking a stand and doing something to keep the Republic. He goes on to heap praise on the sentence in the Declaration of Independence’s preamble that he says, “articulates the theory of American government in a single passage that has been hailed as ‘the greatest sentence ever crafted by human hand.’” “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” The Chief Justice writes that this sentence, “enunciated the American creed, a national mission statement, even though it quite obviously captured an ideal rather than a reality, given that the vast majority of the 56 signers of the Declaration (even Franklin) enslaved other humans at some point in their lives.” Then, the Chief Justice goes down a legal rabbit hole, discussing how many of the Founding Fathers were lawyers, many of whom went on to become judges, including Supreme Court Justices. Some of them turned out to be of questionable character, like James Wilson, who spent much of his life trying to evade his debtors. Roberts dwells on Justice Samuel Chase, whose impeachment I also discuss in my book. The Chief Justice makes the same point that I do: the complaints against Chase involved political disagreement with his judicial decisions. But he was not convicted on the articles of impeachment, because disagreeing with a judge’s decisions isn’t a basis for removal from office. The decision forms the basis of the judiciary’s independence and ability to rule on the cases before them based on the facts and the law, without fear of political interference. Again, Roberts recites the incident without drawing any conclusions, perhaps leaving it to judges across the country to infer that he supports them. But at a time when the country needed a resounding defense of judicial independence in the face of criticism by this administration, it simply didn’t get it from the Chief Justice. The moment requires something more than bland understatement. The Chief Justice touched on some of the most important issues the judiciary faces today, without ever getting to the point. Reading the report, you wouldn’t know that the judiciary has been, quite frankly, under attack by this president. He writes as though he bears no responsibility for handing over unprecedented power to the president, to say nothing of the delay and ultimate grant of immunity from criminal prosecution that facilitated Trump’s return to office. Roberts acknowledges none of that. Instead, he lauds judicial independence, without ever saying that it’s only necessary for him to do so because the president and his minions are challenging judges whose decisions they dislike, as though that’s how this is supposed to work. “The Declaration charged that George III ‘has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.’ The Constitution corrected this flaw, granting life tenure and salary protection to safeguard the independence of federal judges and ensure their ability to serve as a counter-majoritarian check on the political branches. This arrangement, now in place for 236 years, has served the country well.” But what about the threats to individual judges because of their rulings? The need for enhanced security for federal judges and their families? All brought about by this administration’s incessant criticism of the judiciary and willingness to single out individual judges for criticism. Roberts doesn’t express outrage, doesn’t even stand up for the institution he leads. To the extent he objects, it’s so “subtle” that you’d have to make the argument for him. Then there is the subject of slavery. Roberts comments that although the Founders were slaveholders, it was acceptable for them to write that “all men were created equal” because that was an aspirational goal, to be fulfilled down the road—essentially, when convenient. As he puts it, “[t]hey meant simply to declare the right, so that the enforcement of it might follow as fast as circumstances should permit.” He seems to feel some need to explain why the Founding Fathers weren’t at fault here. He acts as though post-Civil War era legislation fixed all of our problems. He doesn’t mention the current effort, in front of his Court, to roll back voting rights, affirmative action, and workplace equity programs like DEI. His touchstones are Susan B. Anthony and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., but again, this is history without any effort to address modern context or current problems. The Chief Justice concludes his report, with a reference to President Calvin Coolidge: “As we approach the semiquincentennial of our Nation’s birth, it is worth recalling the words of President Calvin Coolidge spoken a century ago on the occasion of America’s sesquicentennial: ‘Amid all the clash of conflicting interests, amid all the welter of partisan politics, every American can turn for solace and consolation to the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States with the assurance and confidence that those two great charters of freedom and justice remain firm and unshaken.’” Roberts adds in his own comment: “True then; true now.” That’s it. No discussion of the reality the country—and the judiciary—faces, which is as disturbing as anything we’ve seen from this Chief Justice. No acknowledgment of what we are all aware of. We are left to take solace in the founding documents. The Supreme Court, not so much. John Roberts leads a Court that includes two members who are credibly accused of accepting expensive vacations and other tributes from wealthy men with an interest in the outcome of cases that come before the Court they sit on. Instead of creating consequences and standing for the adoption of a binding ethics code, the Chief Justice has allowed those wounds to fester and the Court’s integrity to suffer. That Court is under attack by the President and his cronies. But again, he offers us the founding documents, inexplicably, the only thing of substance he has to offer in a year where the courts fell under political attacks. My October post, When They Bukele The Courts, is just one of many examples of the open hostility the courts faced. The Chief Justice’s end of year statement acts as though none of that happened. In March, Roberts spoke out, a rare moment, when judges were threatened with impeachment. He did it with his back to the wall, when a failure to speak up could have been seen as tantamount to agreement. But as I wrote at the time, it was premature to welcome him to the resistance. He is still the man who shook Donald Trump’s hand before this year’s State of the Union address, even though looking extremely uncomfortable. “Thank you again. Thank you again,” Trump said to John Roberts, before awkwardly slapping him on the shoulder and intoning, “Won’t forget it.” He is still the man who wrote in Shelby County v. Holder, the case that resulted in the demise of significant parts of the Voting Rights Act, about gains made in voting in communities of color across the country, even as he proceeded to gut. His words here sound nice, but they ring hollow. What is a Chief Justice to say in troubled times? It’s the role of the Court to stay out of politics. Still, we’re entitled to expect more from a man who has risen to the highest judicial office in America. Maybe the truth? Is that too much to ask for? Instead of cloaking himself in the mantle of history and self-righteousness, a little plain, unambiguous truth and clear commentary on the challenge the judiciary faces today would have done so much. A little courage. But regrettably, he doesn’t seem to have caught any of that. Thank you for being here with me. I know you have lots of choices about where to get your news and analysis. I appreciate that you’re spending some of it with me. Your paid subscriptions make it possible for me to devote the time and resources it takes to write the newsletter. I’m proud that we’ve built a community together that’s dedicated to keeping the Republic. We’re in this together, Joyce You're currently a free subscriber to Civil Discourse with Joyce Vance . For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Friday, January 2, 2026

The Chief Justice's Report on the State of the Judiciary

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Welcome to The Georgia Flyover

You are now officially subscribed to The Georgia Flyover – Y'all ready! ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

17 Personal Finance Concepts – #5 Home Ownershippwsadmin, 31 Oct 02:36 AM If you find value in these articles, please share them with your ...

No comments:

Post a Comment