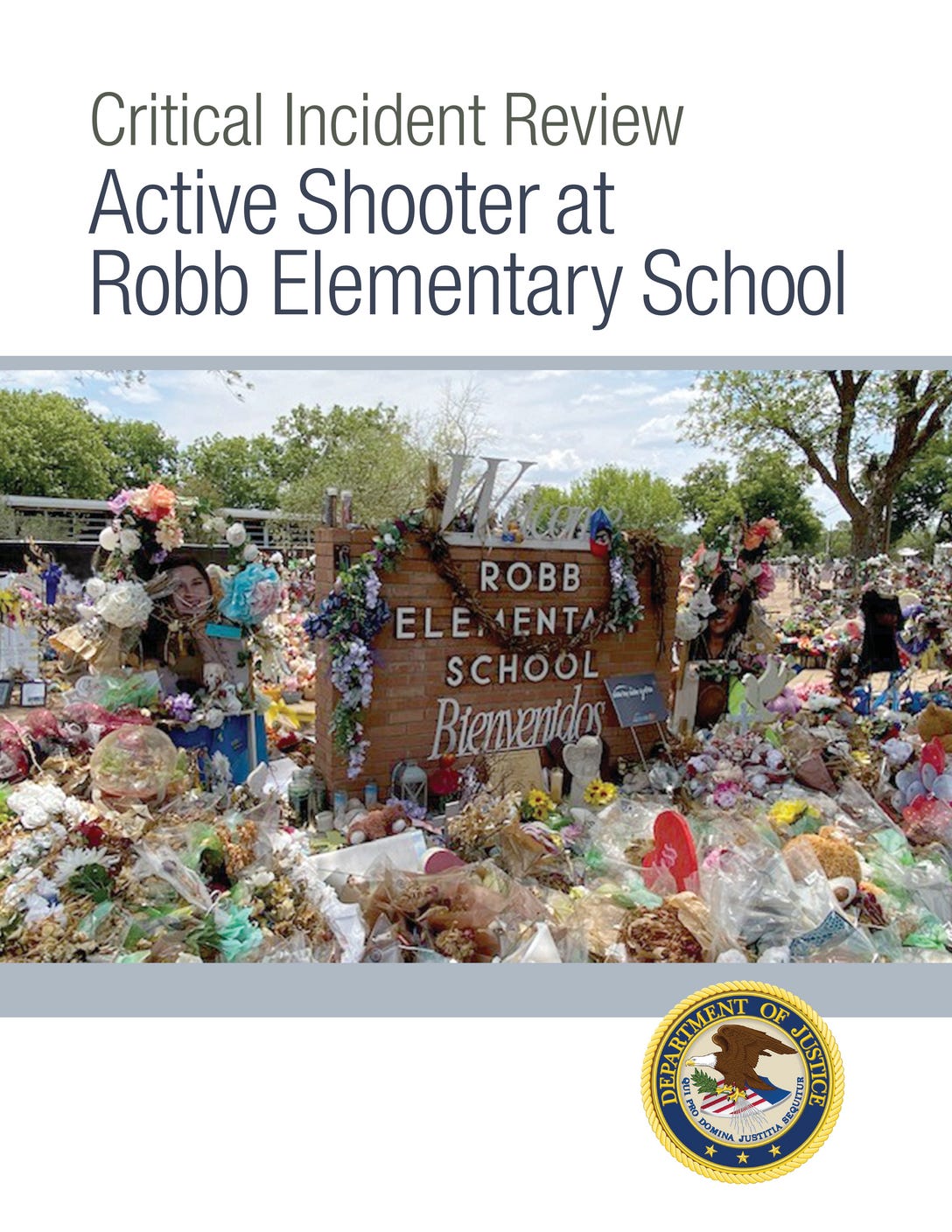

If you’re seeing this shortly after I send it at 9 ET, Katie Phang and I are about to do an impromptu Substack live. Come join us. Robb Elementary School remains closed, but it’s still standing, a constant reminder of the day a school shooter took the lives of 19 fourth graders and two of their teachers in Uvalde, Texas. There is a memorial of 21 crosses and flowers near the school sign. Officer Adrian Gonzalez, who pled not guilty, is on trial for failing to do enough to protect the students and their teachers. Law enforcement waited over an hour before they confronted the shooter. Gonzalez is charged with 29 counts of child endangerment. He is alleged to have neglected his duty and training during the chaotic response to the shooting. On Monday, January 5, the Judge seated a jury of 12 jurors and four alternates who are currently hearing the case. Despite the fact that the trial was moved to Corpus Christi, about 200 miles from Uvalde, at the defense’s request, it was not easy to find jurors who would agree to be objective about the case. One of the potential jurors who was dismissed told the Judge, “They were only protecting themselves more than they were protecting the children. I would have sacrificed myself to save them, but they didn't. They just sat there.” Other potential jurors in the courtroom reportedly cheered and clapped in agreement. Judge Sid Harle explained that he was looking for jurors who could be impartial. It goes without saying that just about everyone who was called to court knew at least something about the shooting, but many of the potential jurors conceded they had already formed an opinion about what happened that day, and about 100 of them were dismissed for cause. The government explained its case in its opening statement, telling jurors they would be asked to consider whether the defendant’s inaction was harmful. He told them that “If there is a duty to act and you fail to act, that’s child endangerment.” That’s the basis for the prosecution, a failure to perform a duty, like the duty to protect that police officers assume. Only Gonzales and former Uvalde schools police chief Pete Arredondo have been charged. Arredondo does not have a trial date yet. So, why Gonzales out of all of the officers on the scene that day? It’s easier to understand why the Chief would be charged. But the prosecution, we learned in opening statements, will offer evidence that a teacher came face-to-face with the gunman before he entered the school and warned Gonzales. The gunman fired at the teacher, who fell when she turned to try and run away. By the time she got up, the shooter was gone and Officer Gonzales was there. She told him, “He’s over there,” and that the officer needed to go after him. Gonzales got on a police radio, described the shooter’s clothing and location and said shots had been fired, but remained by the side of the school instead of taking any action. Police waited 77 minutes before going on the offensive against the shooter, even though almost 400 officers had gathered. The charges against Gonzalez and Arredondo came after DOJ issued a report that concluded local police commanders and state law enforcement were at fault for not immediately entering the classroom and killing the gunman, which would have saved lives. The trial will likely finish up by the end of this week. If convicted, Gonzales faces up to two years in prison. A jury declined to convict on a similar charge brought against Officer Scot Peterson after the Parkland, Florida, shooting, although the facts there were more ambiguous. In the Florida case, there was testimony from students and others that the situation was confusing, and it wasn’t entirely clear where shots were coming from, although the prosecution vigorously disputed those accounts. In the Uvalde case, the Justice Department report and the fact that officers remained outside for over an hour while a mass shooter was stalking students may have pushed prosecutors to indict this case. But there was also tremendous pressure from the community to hold someone accountable for its loss in the face of such utter tragedy and inaction from the people they expected to protect their children. At best, a case like this is difficult and emotional, and it’s hard to assess whether every single member of a jury will agree to hold this police officer accountable. As one of the dismissed potential jurors put it, “Are you saying this man is the whole problem? You are sticking it on his shoulders alone? How many of them were out there? They should all be sitting there with him.” Gonzales has not taken the stand so far, but the prosecution played his interview with Texas Rangers, conducted the day after the shooting, for the jury. Gonzales explained that he “never saw the shooter because of the location where he responded. He responded initially to the south side of the building as the gunman was opening fire in the parking lot.” When officers finally went in, he was part of the vanguard that tried to make its way into the classroom where the gunman was, but officers pulled back when he fired on them. The defense is over, and the government is in its rebuttal case. The last witness of the day was the father of a student who survived the shooting. These cases are hard on everyone. And trying to assign blame after the fact happens, when it’s too late—too late for the victims and too late for the families. The shooter used an AR-15 that came from a local sporting goods store. He purchased the gun and the ammunition legally. Juries will decide whether either of the two officers charged bears responsibility for what happened. We may know their decision on Gonzales later this week. But as we all know far too well, the fault really lies with laws and lawmakers that make it far too easy to get this kind of weapon. After Uvalde, Congress passed a modest bipartisan law that made it easier to do checks on adults under 21 who were buying guns, but a measure to ban assault weapons never made it to a vote. Texas’s Governor, Greg Abbott, rejected Uvalde families’ request for new gun control measures. He asserted that raising the minimum age to purchase weapons like the one used in the school shooting would be “unconstitutional.” If you want to hold someone accountable, the people who make it so easy to buy these weapons would be a good place to start. Thanks for being a part of Civil Discourse. Tonight’s post is one I wanted to write so everyone would be aware of the case before the verdict is reported. There has been very little coverage of the trial outside of Texas. If you appreciate posts like this, I hope you’ll consider subscribing if you aren’t already. Paid subscriptions make it possible for me to devote the time and resources it takes to write the newsletter. We’re in this together, Joyce You're currently a free subscriber to Civil Discourse with Joyce Vance . For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Wednesday, January 14, 2026

A Painful Case: Prosecuting an Officer Who Was Part of the Slow Response in Uvlade

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

-

17 Personal Finance Concepts – #5 Home Ownershippwsadmin, 31 Oct 02:36 AM If you find value in these articles, please share them with your ...

No comments:

Post a Comment